A Fierce Society’s Warlike Architecture

The central debate in the study of Hittite architecture is whether their designs were the product of abstraction or a reflection of function and landscape. The Hittites civilization emerged in the third millennium B.C.E., when Indo-European people started to assimilate the indigenous population of Asia Minor. The Hittite state [Kostof, S., 199)] eventually became the most important military power of Ancient Middle East. [Kerrigan, 2011] These “Spartans” of Anatolia were fierce worriers; by 2000 B.C. they expanded their territory south into Syria and Palestine, and east into northern Mesopotamia. [Nutt, 1903]

The Hittites also thought and subsequently signed the first known peace treaty with Egypt [Kerrigan, 2011]. They even invaded the Babylon, albeit briefly.

Society and cultural characteristics

The Hittites’ military exploits greatly influenced their society, cultural characteristics, and art. These elements, in turn, collectively informed their architectural style and practices. The fierce lion and sphinx sculptures guarding the entrance into the city through the renowned corbelled arch gateway symbolized the strength of the nation and their fierce, yet practical architecture. A similar emphasis on strength and practicality was evident in the main elements of Hittite architecture, including fortification systems, temples, administrative buildings and residential houses, in each instance however, form ultimately followed function and the surrounding landscape.

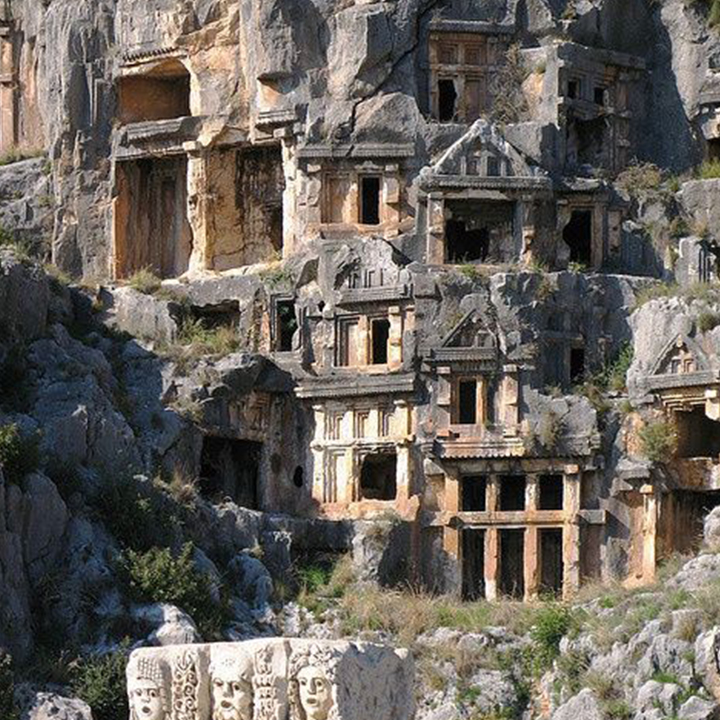

Striving to secure themselves against invading armies, the Hittites fortified each of their cities. Chief among them was Hattusas, the Hittite capital. Situated in the rocky hills [Kostof, 1995], its position in the natural landscape allowed the Hittites to spot enemy forces long before they reached the city. The hilly terrain also slowed the enemy’s advance, giving the Hittites more time to mobilize their own forces. Fortifications enhanced this defensive position. To protect the city, the Hittites built a double shell wall around it. These walls were constructed using so-called “cyclopean masonry”, in which large limestone blocks of different sizes and shapes were fit together (or worked in with hammer) without any mortar, leaving minimal clearance between stones. The result was a robust structure that proved difficult to breach.

The walls’ path followed the landscape’s natural hills. This helped facilitate their construction. It also made the walls appear taller by harnessing the hills’ height. Although the absence of a predetermined geometric form might suggest some degree of abstraction, martial practicality provides a better explanation for this union of function and landscape. It also appears to have influenced the esthetic, with the walls’ rough stones making the city look fierce and impregnable.

Similar factors informed the architecture of Hittite temples. Their designs did not follow any standard conventions, such as symmetry or uniformity. Much like the fortification described above, one could argue that it was abstract. Yet each temple’s form was ultimately influenced by its function, relationship with surrounding landscape, and martial character of Hittite society.

Temple I at Hattutas is a case in point. The practical and minimalistic, the temple’s sanctuary was surrounded by storerooms and repositories [Kostof, 1995], that mimicked city’s fortified walls. The Temple had other protective features as well. For example there was no direct path leading from the Temple’s entrance to the sanctuary. Instead, vestibules situated around the perimeter of the sanctuary lead to the sanctuary entrance. Finally the Temple’s construction was rather economical. There were no lavish decorative materials like those found inside Egyptian Pyramids during the same period. In a great contrast with the Pyramids Temple’s sanctuary was also full of natural light from two windows that directly illuminated the statue within. [Kostof, 1995]

Function and landscape were also the driving considerations in residential and administrative architecture. Hittites’ housing was usually comprised of contiguous homes clustered around common central courts. [Kostof, 1995] Like much of Hittites’ architecture these buildings did not adhere to a regular construction pattern. They did possess familiar construction techniques, however, including a half-timbered structure designed to cope with Anatolia’s frequent earthquakes. Similar building practices are still used in earthquake-prone regions today. [Kostof, 1995]

This emphasis on function and the environment does not mean that Hittites society lacked abstract or artistic influences. Despite the practicality of their architecture and preoccupation with martial activities, Hittite society produced artists, craftsmen and early scientists. Hittites decorated walls with beautiful carvings, paved streets, invented the drainage channel system, and exported copper, bronze and iron to neighboring civilizations. Despite these attributes, however, Hittites did not impose a geometric structure on their architecture in the same manner as the Egyptians. Nor did they invest time and resources transporting beautiful decorative stones from distant lands and polishing them to perfection. Instead, Hittite architecture followed natural landscape, used local building materials and emphasized function as the basic for form. It was as befits a martial society practical.

Several elements of the Hittite approach are evident in contemporary architecture. Like the Hittite, contemporary architects embrace the use of local materials and the need to integrate buildings into the surrounding landscape. This approach is more than simply practical, however. Although such techniques may reduce costs and improve the function, there is a growing realization that merging a building with its environment also brings a unique harmony to the site. In this sense, contemporary architecture views function and landscape both from a practical standpoint and from an abstract aesthetic one as well. Thus, Hittites’ architectural objects might have been the ancient predecessors of contemporary buildings like California Academy of Sciences by Renzo Piano, “Fallingwater” building and Martin Country Center by Frank Lloyd Wright, or Therme Vals by Peter Zumphor among others.

Bibliography

Kerrigan, M. (2011). Ancients in Their Own Words. New York: Marshall Cavendish Benchmark.

Kostof, S. (1995). A history of Architecture. New York: Oxford Univercity Press.

Leopold Messerschmidt, Ph. D. (1903). The Hittites. London: David Nutt.