The Bauhaus Building: Complex Simplicity

Architect Walter Gropius designed the Bauhaus Building specifically for the Bauhaus School in Dessau, Germany. His design reflected the school’s broadest ideals, including the creation of “a new guild of craftsmen, without the class distinctions that raise an arrogant barrier between the craftsmen and artist.” To that end, Gropius sought, in the words of the school’s manifesto, to “conceive and create the new building of the future, which will embrace architecture and sculpture and painting in one unity and which will rise one day towards heaven from the hands of a million workers, like the crystal symbol of a new faith.” The building captured and articulated the dilemma of 20th Century architecture, however: how to address the consequences of industrialization and the resulting confrontation between individualism and universal design.

Soviet Constructionism and De Stijl

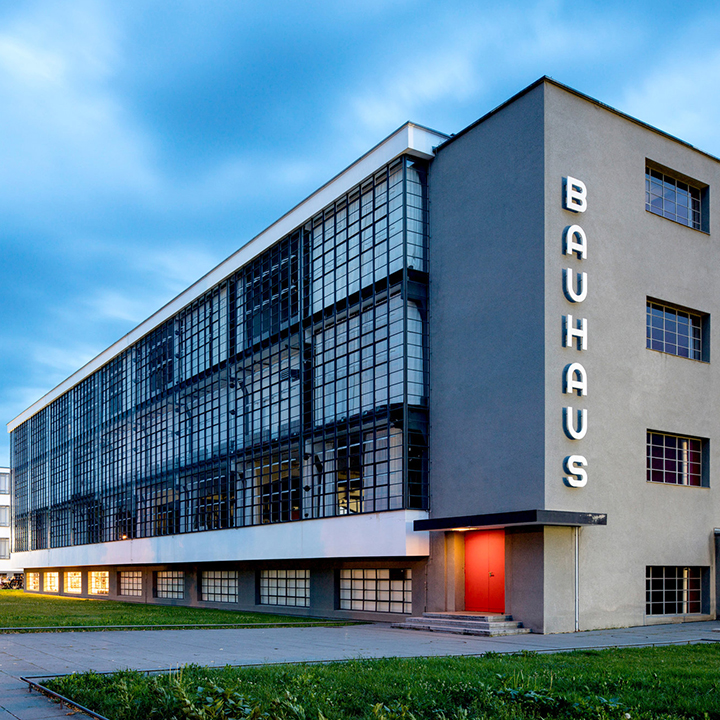

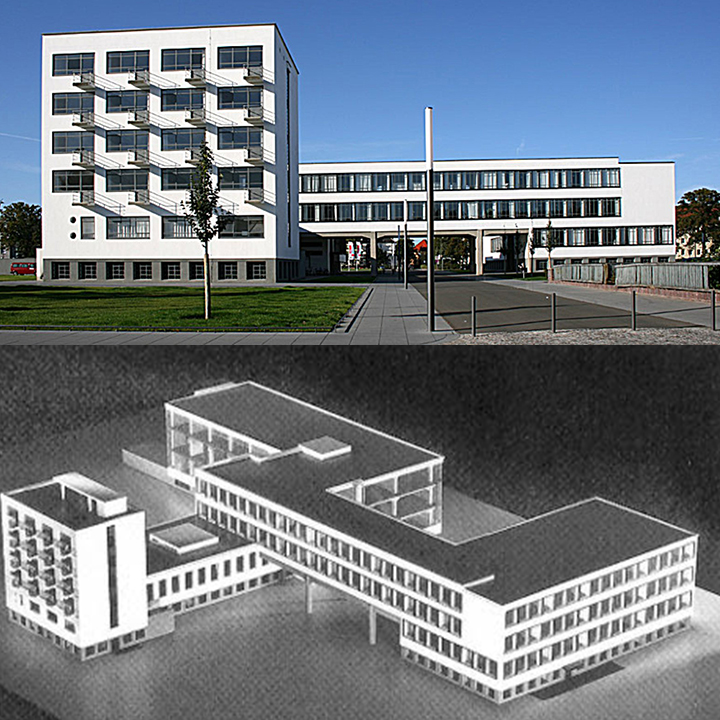

The Bauhaus Building displays the influence of Soviet constructionism, an artistic and architectural philosophy that embraced abstract, futuristic forms as an expression of socialist ideals, and De Stijl a Dutch movement that emphasized pure abstraction and reductive simplicity to express notions of harmony and order. To these ends, Gropius linked separate rectangular volumes—each different in size, each designed according to their particular function—into a single sprawling complex. The complex, in turn, formed a straight angle utilizing perpendicular formations. This allowed for the building to be “experienced from any angle.” [Curtis, 194.6] As Alan Colquhoun observed, the school building was “the first major structure realized by Gropius in the new ‘dynamic functional’ manner”—a phrase that emphasizes the structure’s unity of purpose and design. [Colquhoun, 196.3]

The Bauhaus Building’s lack of ornamentation communicated similar themes. Gropius arranged façade elements asymmetrically while maintaining rhythmic balance. Glazed windows articulated by square metal frames partially revealed load-bearing columns of the building—and artistic acknowledgement of a new structural technology. At times recessed, these columns “laid flush with the façade” [Curtis, 196.2] articulated white concrete walls and levels of the building. Finally, windows unified different parts of the building, bringing it together into a coherent whole. Although each element was simple and abstract, the resulting system proved complex and dynamic. In this sense, it used elements of universal design to produce a uniquely individualized structure.

The structure of the Bauhaus Building also captures this juxtaposition between the universal and individual. At first, the complex appears to be an amalgamation of distinct buildings connected by wings or bridges. Gropius connected the school and workshop using a two-story bridge, with administration located on the lower level and offices for senior scholars (namely Adolf Meyer and Gropius himself) on the upper level. A similar wing connected the dormitories and school building while housing a dinning area and an assembly hall. The resulting layout mixed form and function in a manner than connected private working and living areas (the individual) through the use of shared public space (the universal).

The Bauhaus Building became the most studied and explored structures of European modernism because it depicts, symbolizes, and in some way answers to the artistic philosophies of the modernism. As Curtis observes, the importance of the building lay in its “precision of formal thinking”–thinking that “marked major step in the maturing system of forms” that would define the “unfolding history of the modern movement.” [Curtis, 196} From the interplay of form and function to the definition and juxtaposition of public and private space, Gropius’ Bauhaus Building did more than simply recognize the 20th Century tension between individualism and universalism. It also sought to reconcile it.

Bibliography

Colquhoun, Alan. Modern Architecture. Oxford: Pxford Press, 2002.

Curl, James Stevens. Encyclopedia.com. 2000. 2012

Curtis, William J.R. Modern Architecture Since 1900. New York: Phaidon Press, 2003.